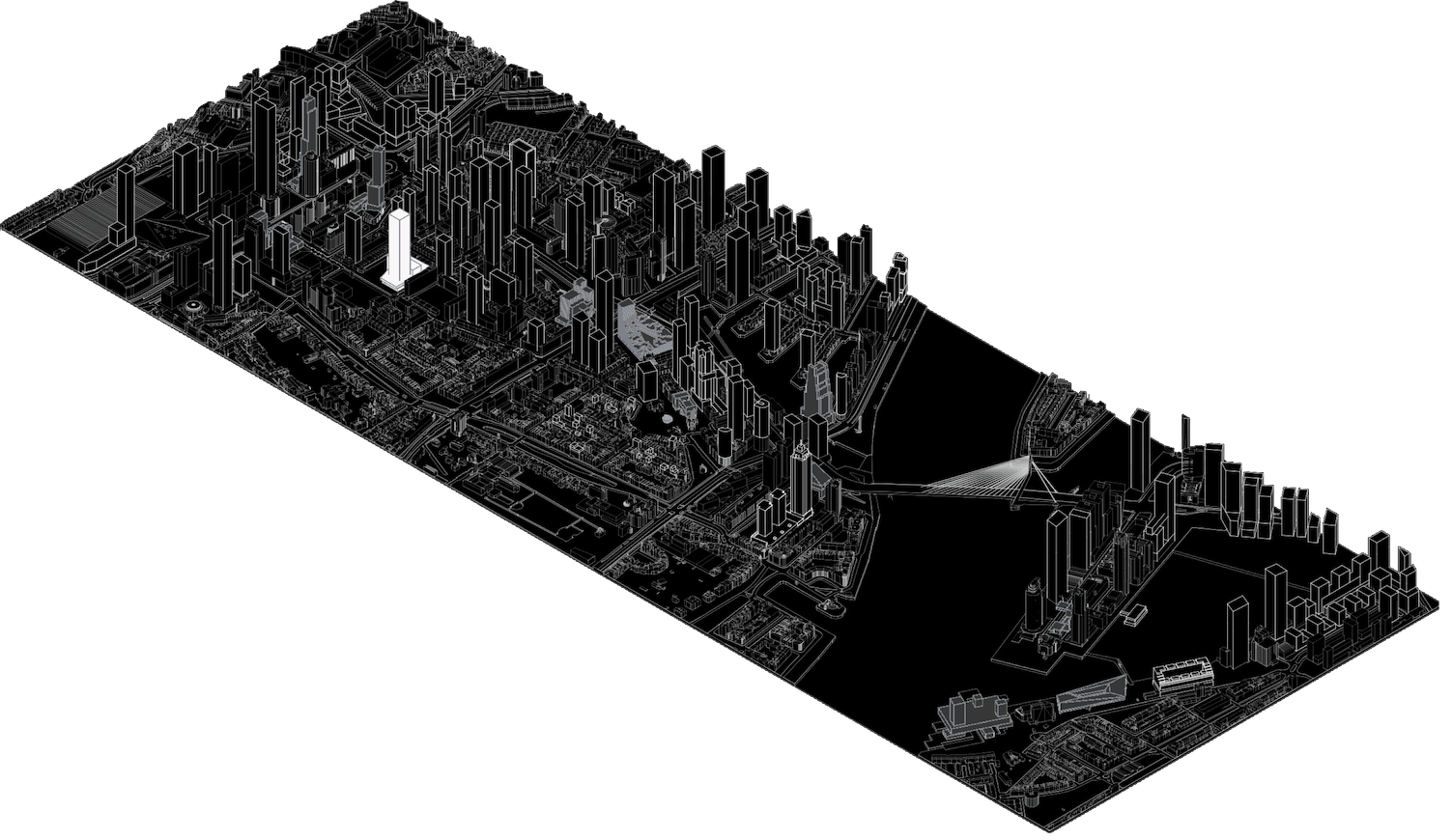

Since the neoliberal implementation in the government plans of Rotterdam in 1987, the vision of the city changed quite radically. Only a decade before the adaptation in 1987, the government rejected high-rise buildings in its city. But since new future plans, called ‘Nieuw Rotterdam’, got approved, Rotterdam adapted an high-rise vision which has made the city as it is today; a modern character and relative tall buildings in Dutch terms. Yet, this high-rise implementation is only a small attribution of the conducted vision that was established in the late previous century. This neoliberal implementation goes further than merely implementing American-like high-rise buildings. It concerns the economics; particularly the globalization of the market and the multinational business trend that defines the contemporary economical appearances of both city and country. Since the drastic changes in city vision, Rotterdam opened up its tertiary economic sector borders and adopted a desire for foreign business.

Hereby it was attempted to upgrade their economical game and compete against the economic prosperity of other cities, both national and international. The city therefore changed quite radically since Nieuw Rotterdam was practically implemented. Its buildings grew, its habitants grew and it became a popular place for tourists. However, the aspect of business, is leaves a lot to be desired. While it started to aim at welcoming more foreign business thirty years ago, Rotterdam today is still struggling to welcome foreign business into its city. One of the primary reasons for this, is that both the city center and its economical heart of the RCD, lacks an economical identity. Rotterdam did have its identity of the industry and the port, yet the neoliberal growth and privatization of those instances led to the translocation outside the city center. In addition to this, the economic sector of industry became less favorable, since the tertiary sector of a business service economy predominates a neoliberal oriented city. The project of the Vertical High Tech Campus explores the promising economical sector of high tech in combination with its research and business aspects in an urban environment as a step towards providing a new economic identity for the city of Rotterdam.

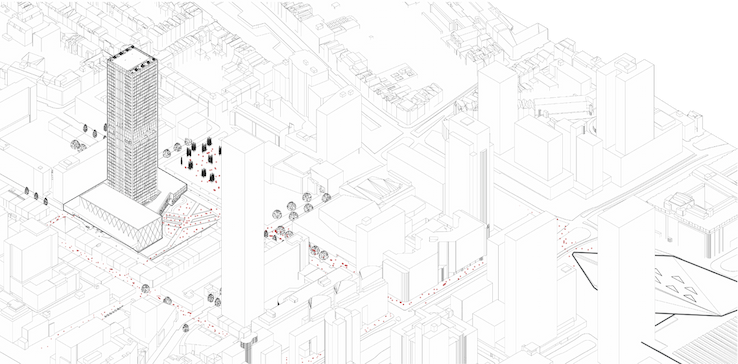

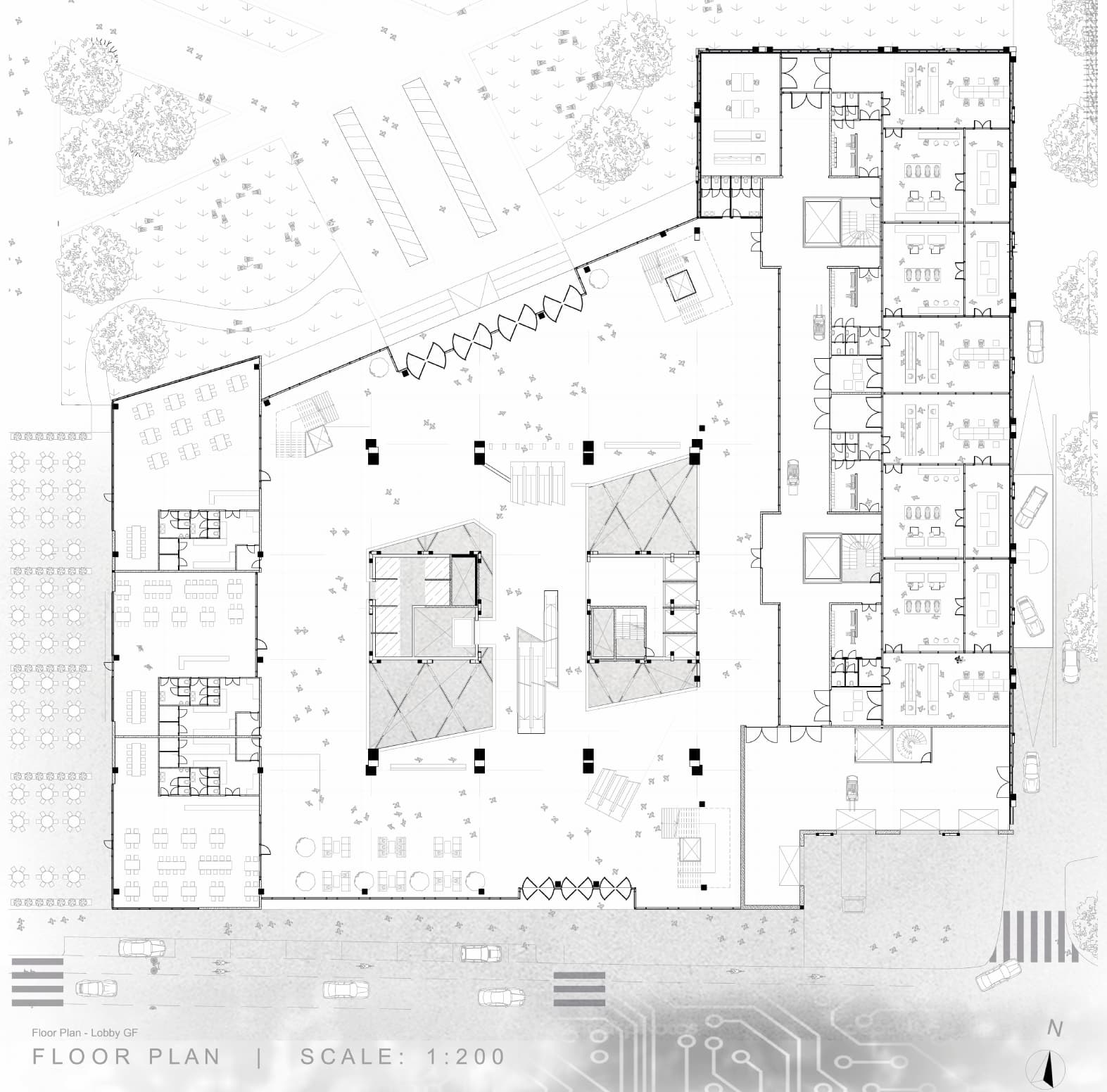

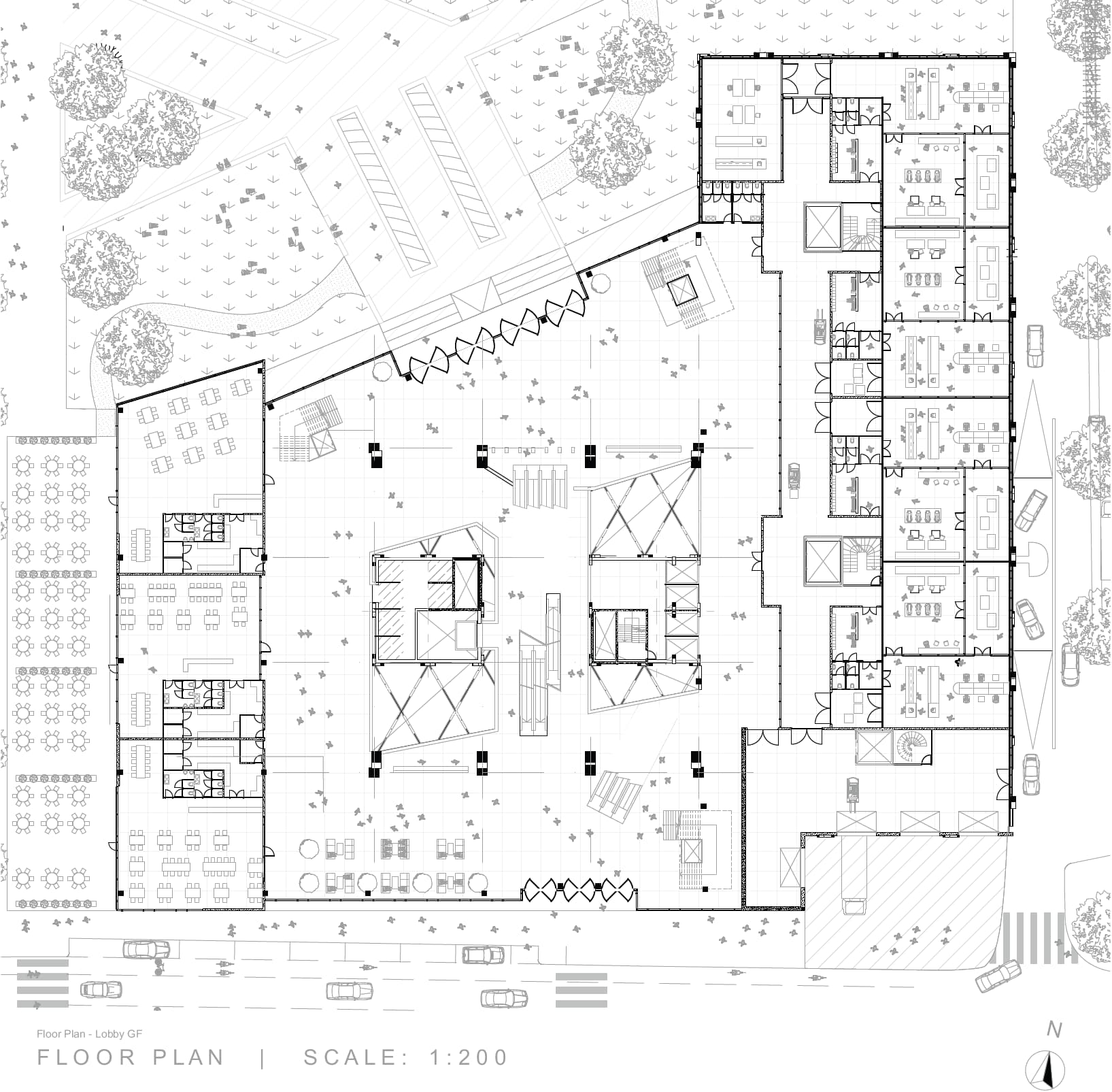

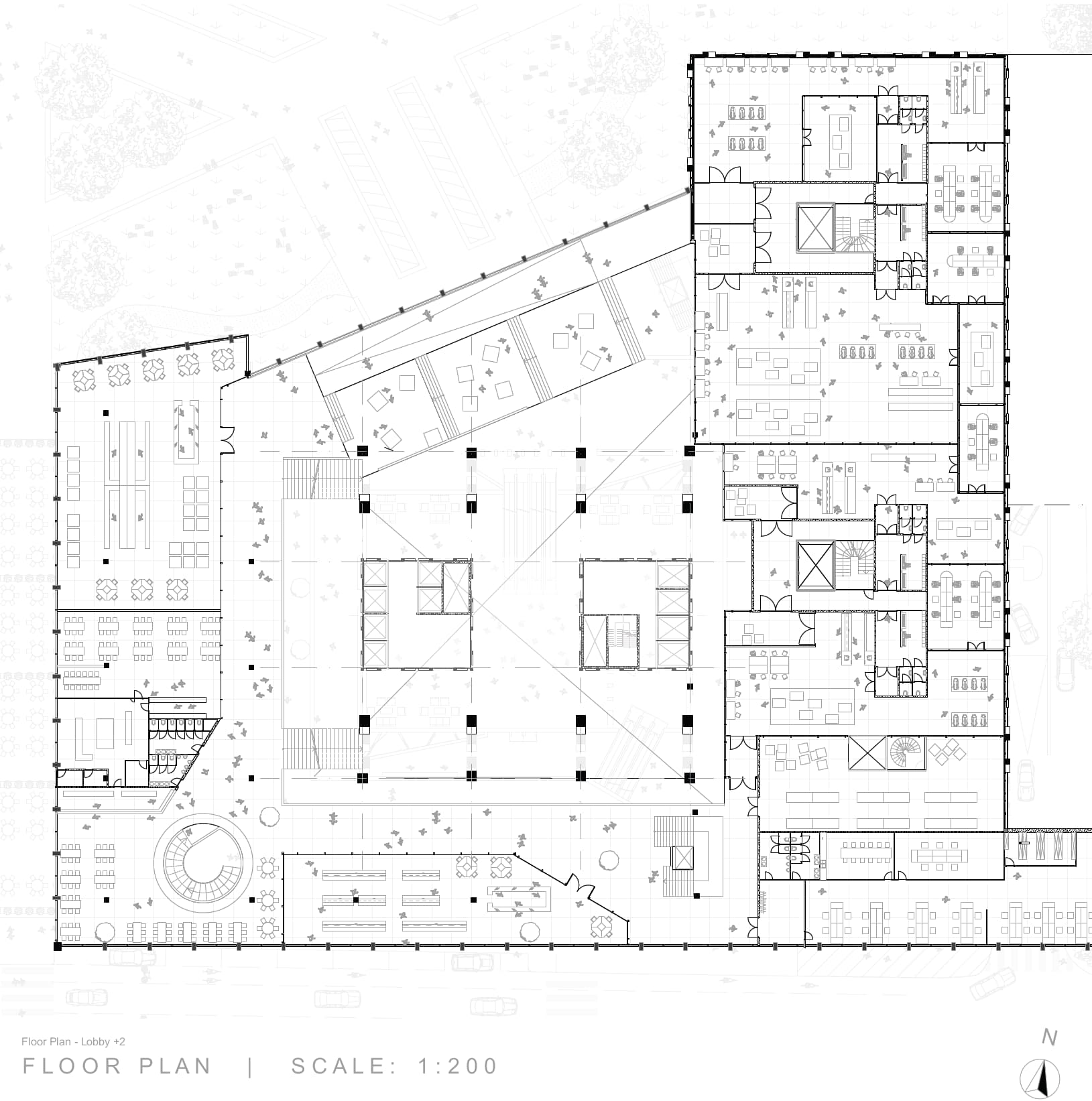

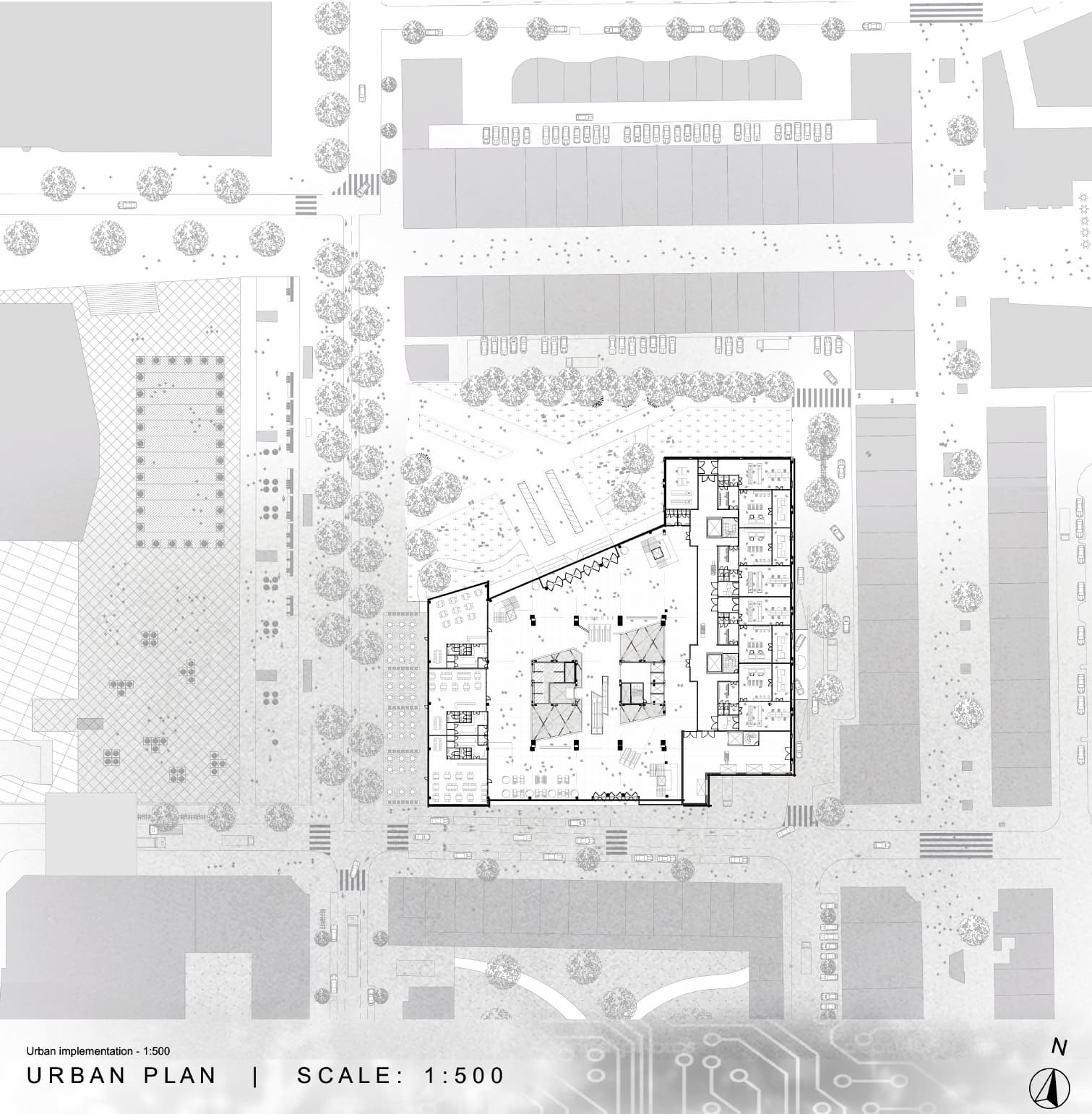

The area of the RCD around the Weena in Rotterdam, marks an economical area in Rotterdam that currently isn’t fulfilling its potential. This central business district provides an unique situation as it is situated as an integrated part of the city, rather than a forced isolated financial district in the periphery of the city. Yet, amidst the lack of an economical identity, the problem of mono functionality and traditional corporate offices dominate this integrated central business district in the city of Rotterdam. The site argument arises from a revision in courtyard, mass and function, to boost the early flamboyant appearance of the Lijnbaan into a more lively area. In here, the project blurs the lines between the corporate northern area and southern amenities area of the RCD. In this way, the campus establishes a connection to the RCD through its mix of both corporate and amenity functions.

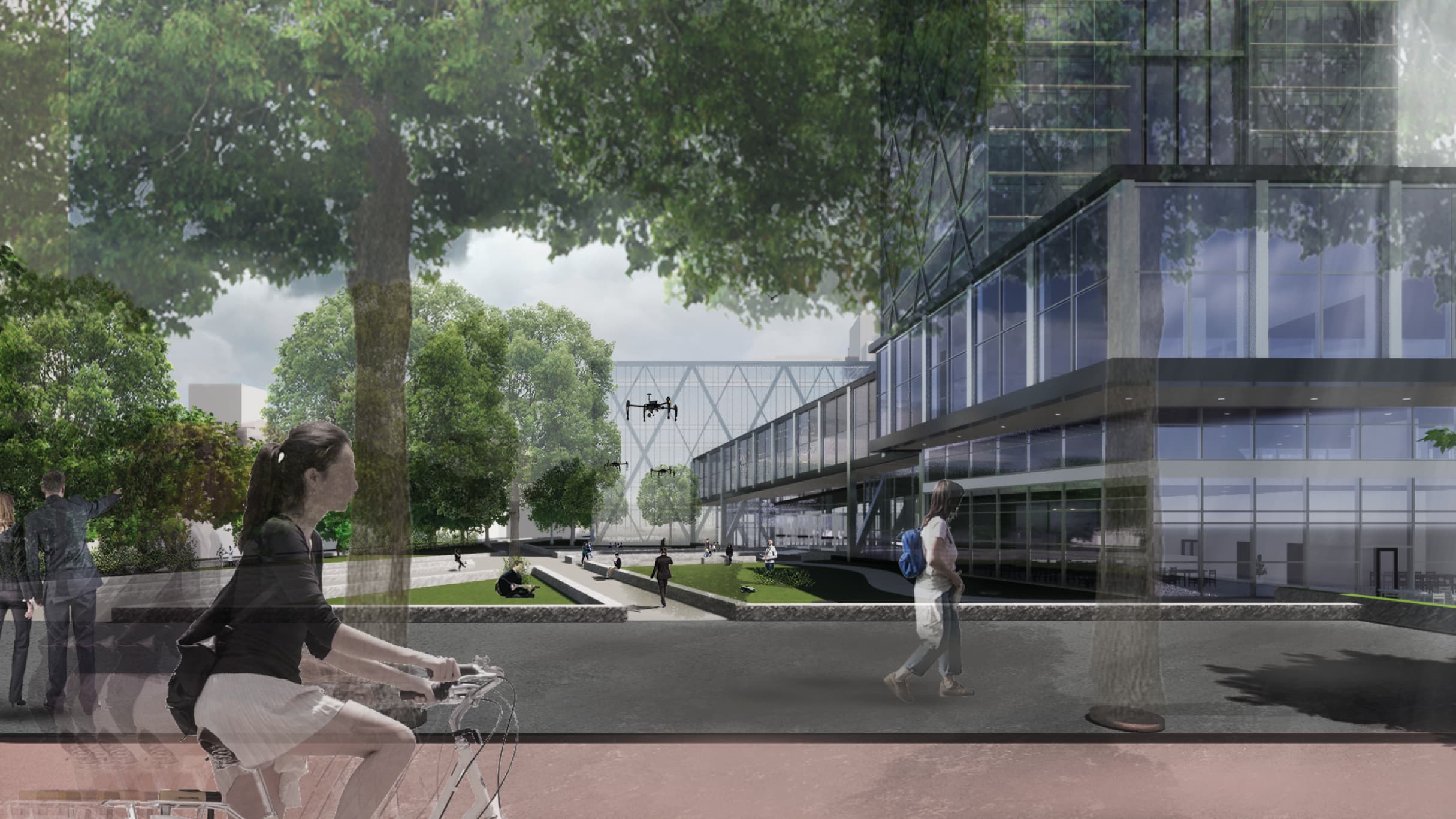

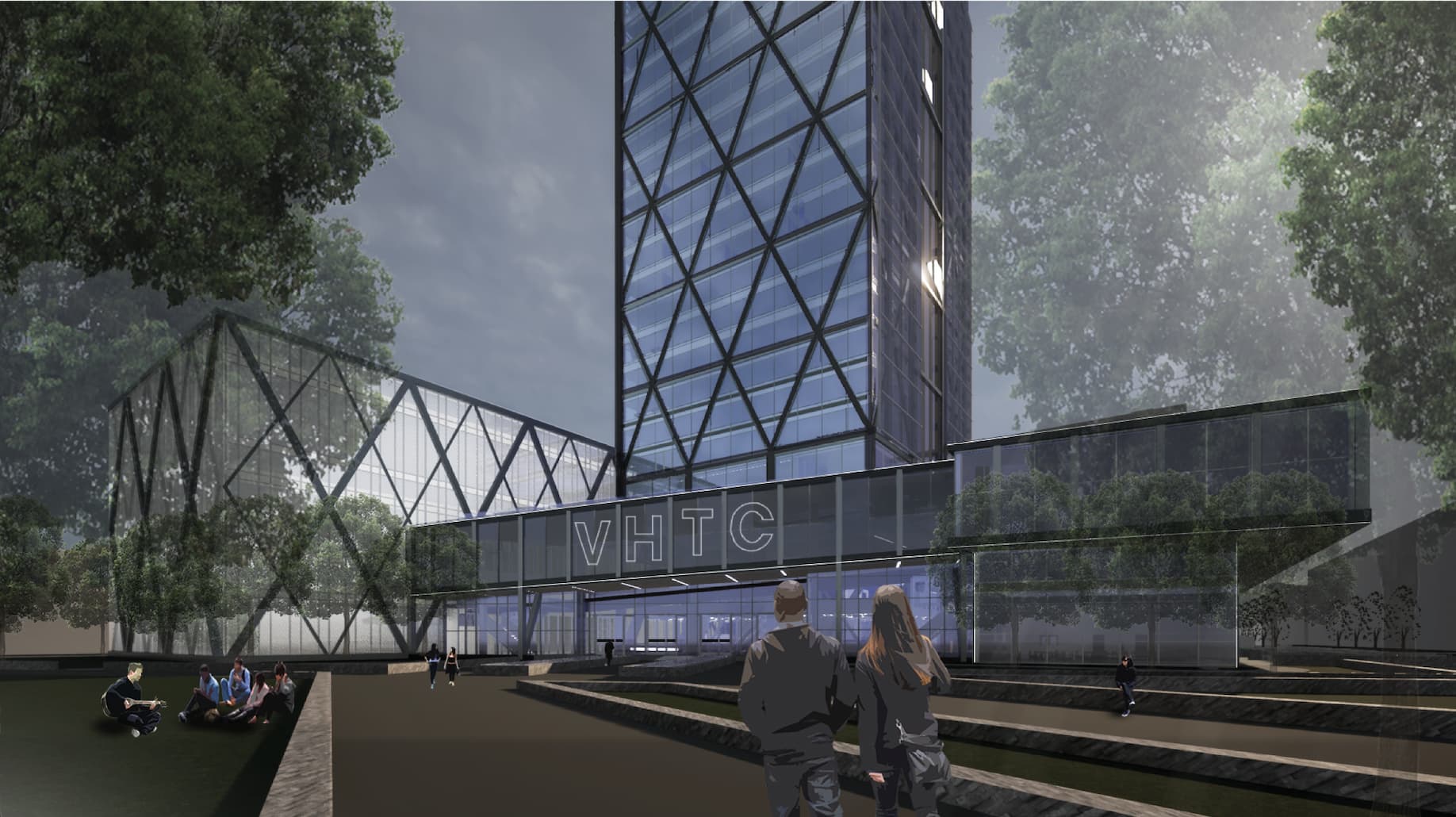

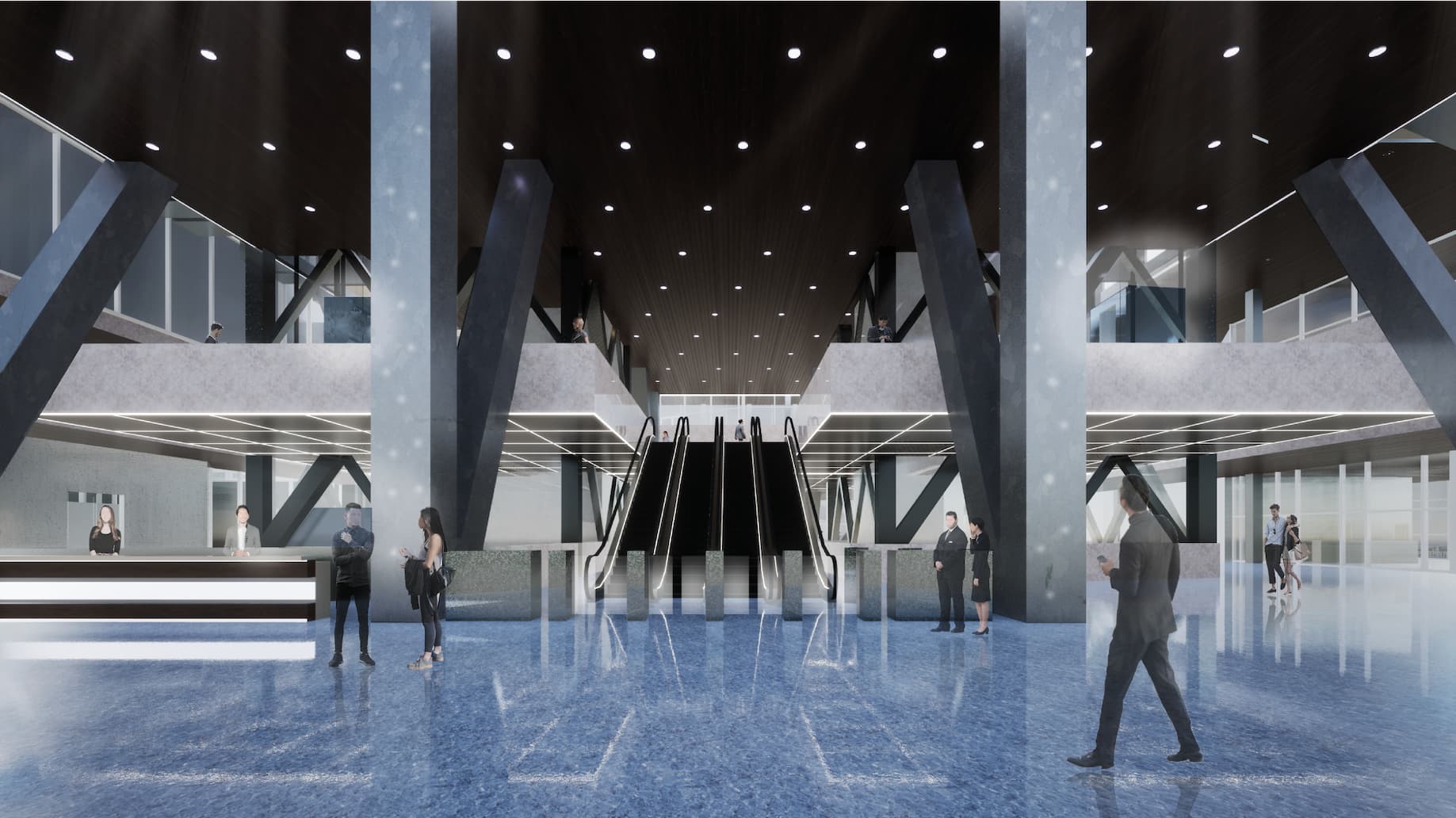

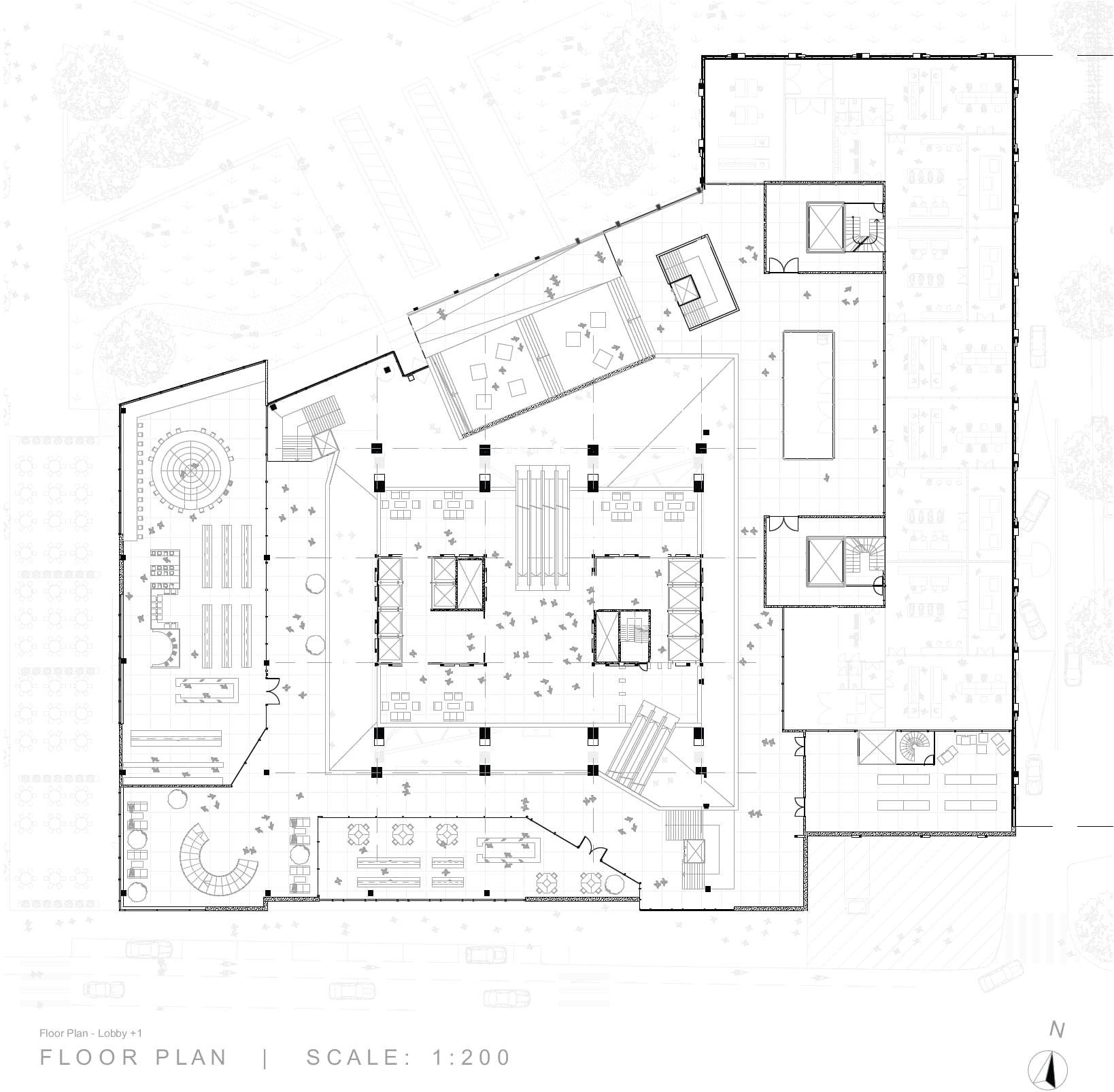

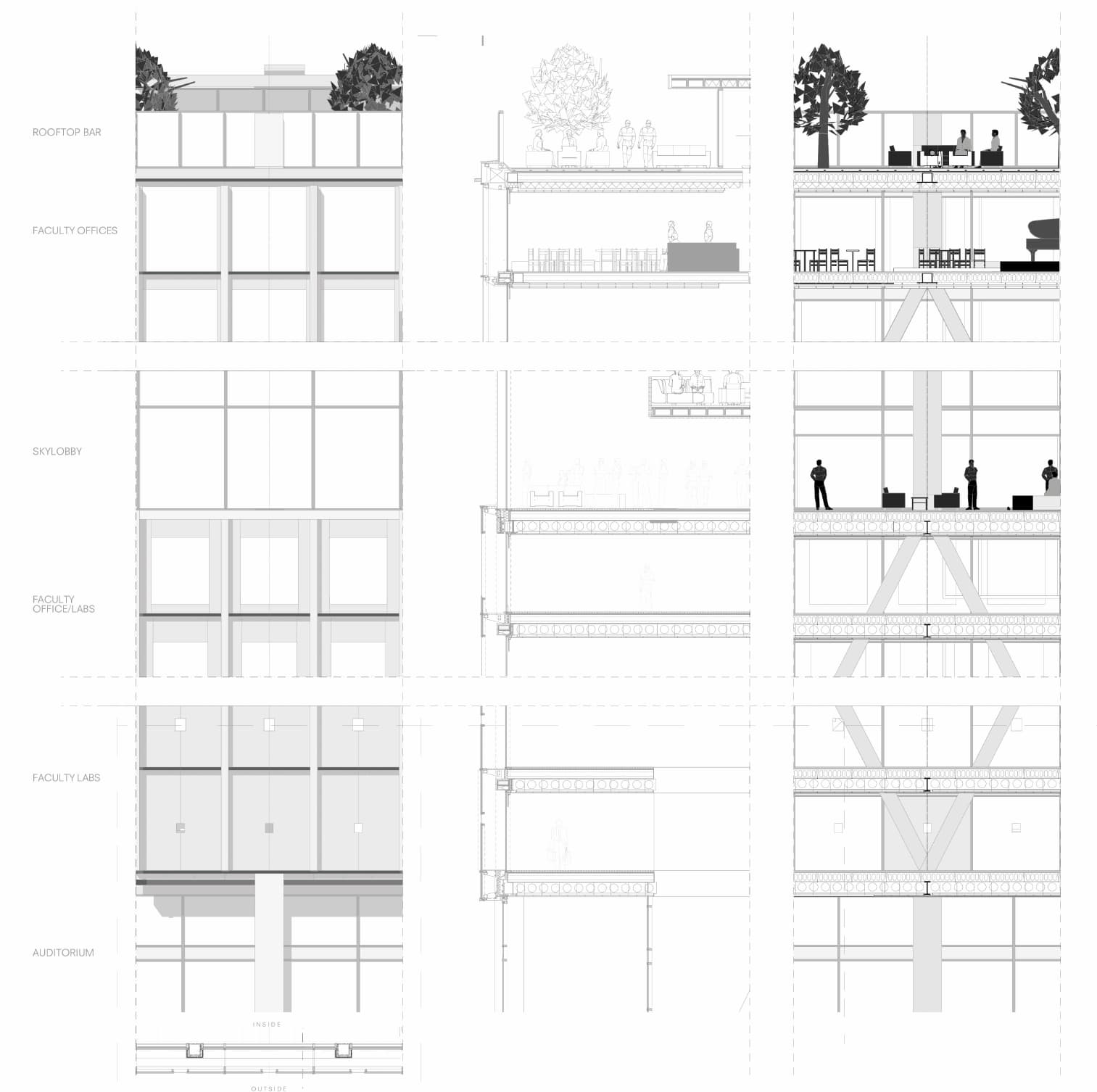

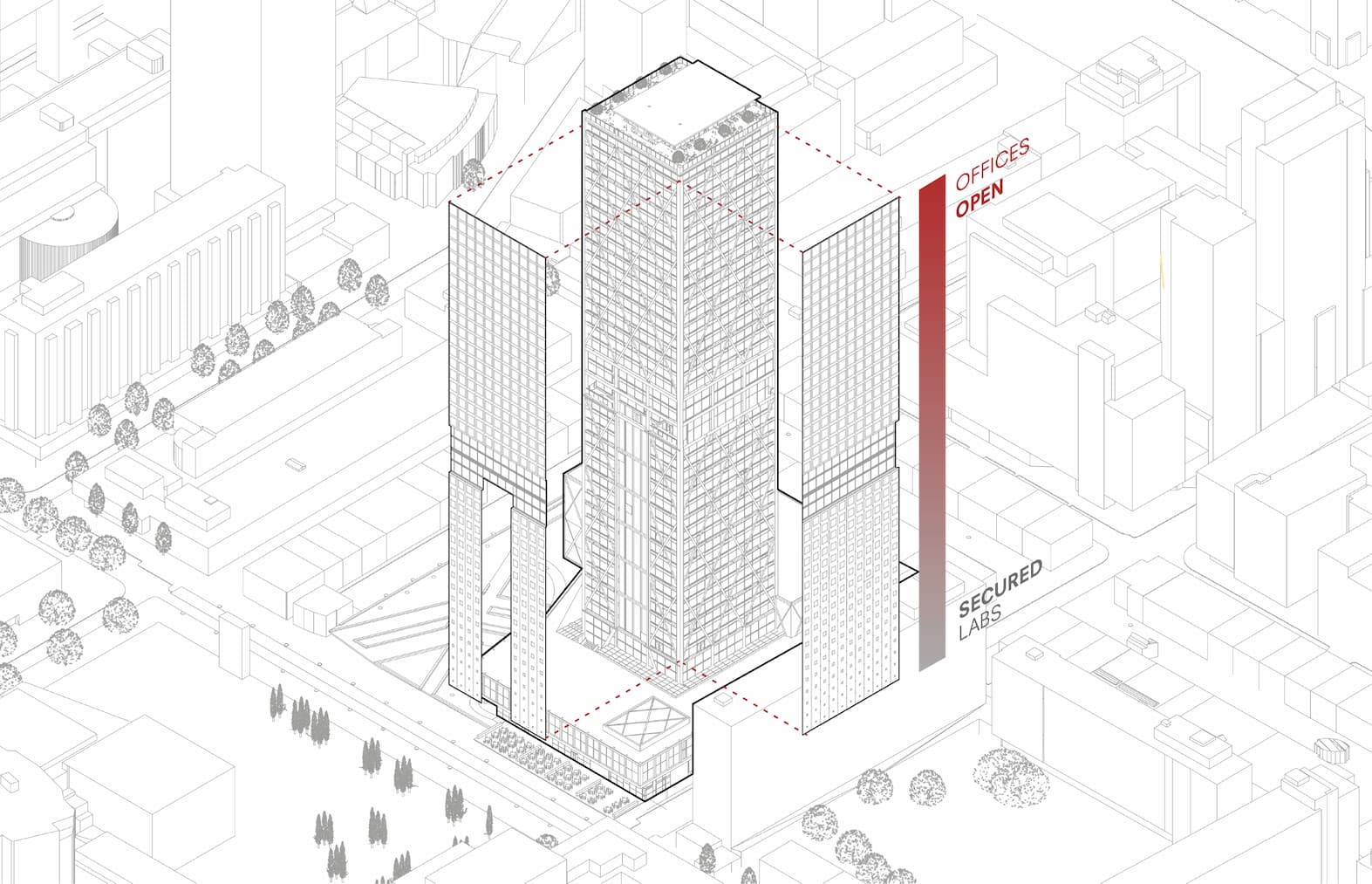

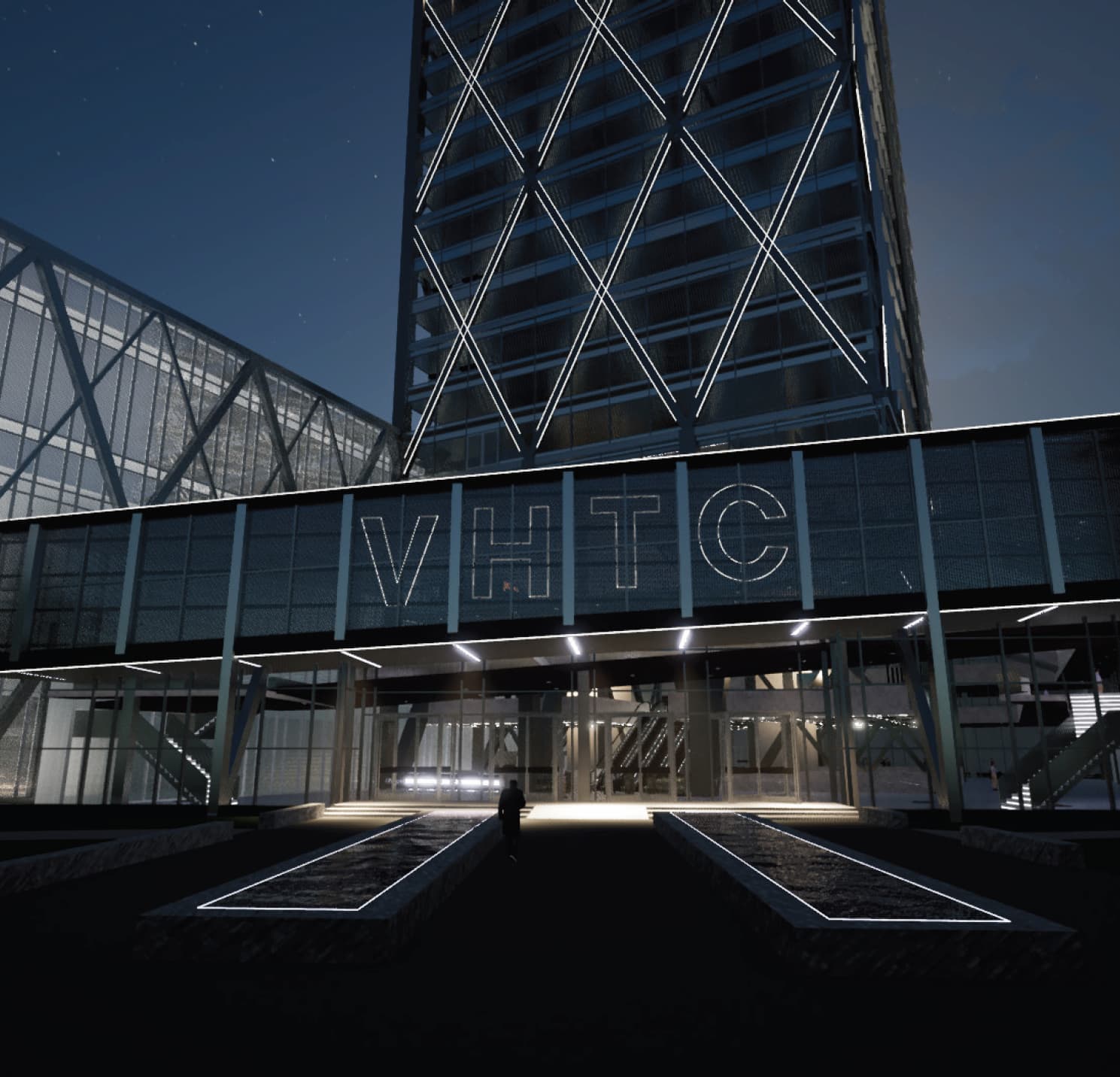

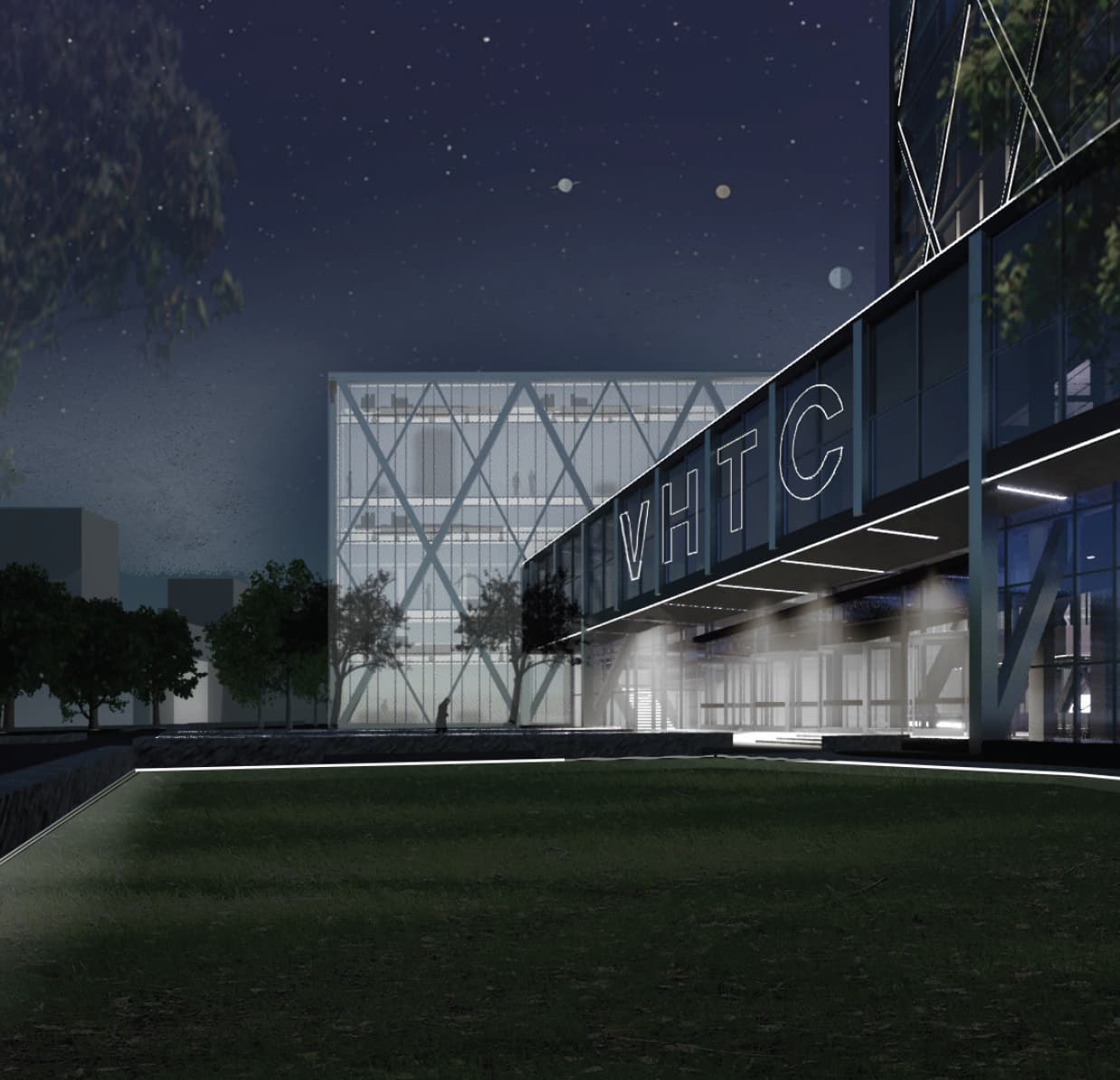

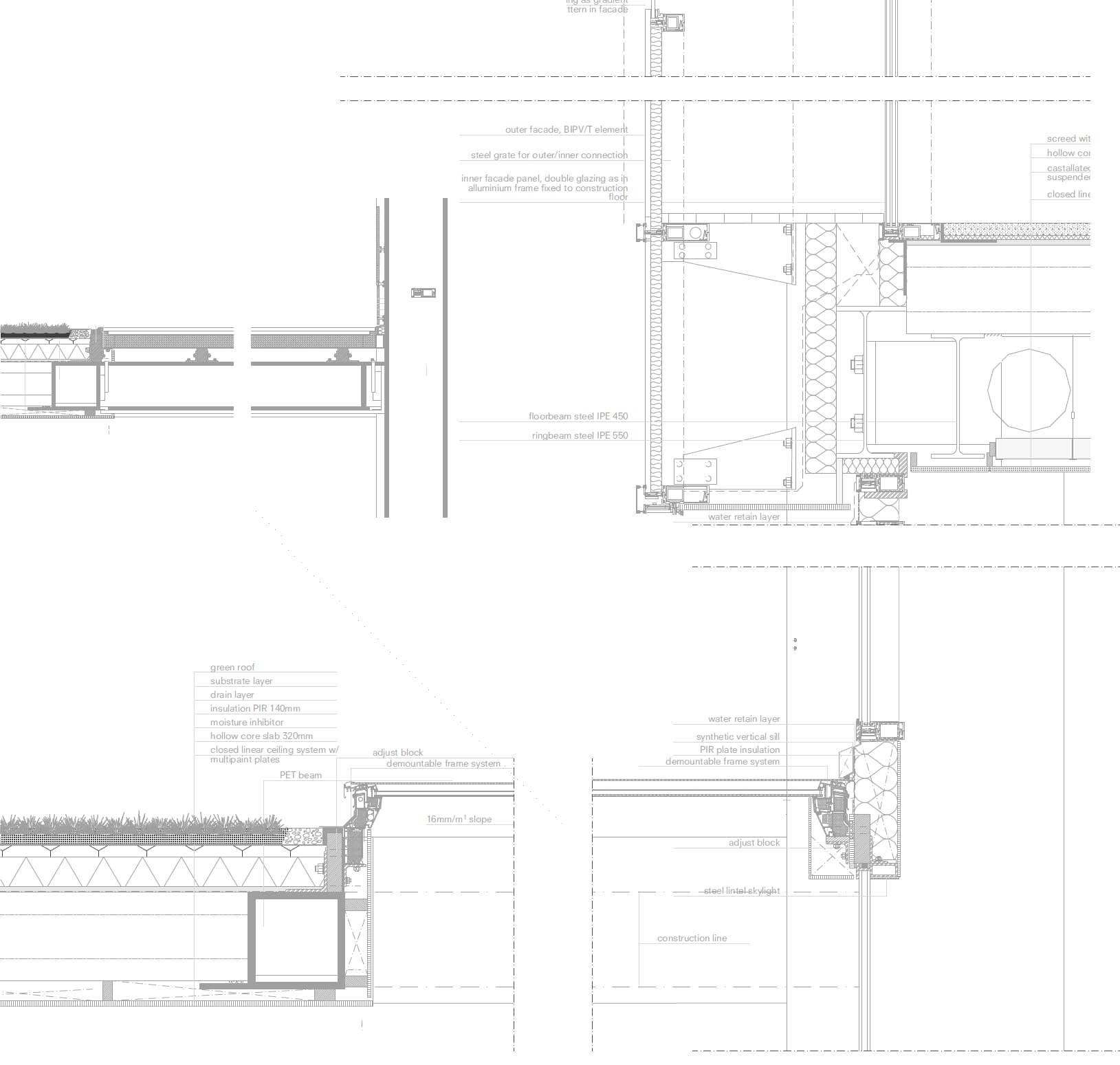

The vertical campus becomes a densified injection in this rather closed area of the city center. The privatized courtyard is reinterpreted as a campus park, to open up the plot to the public flow. In here, the lobby serves as an extension of this new public domain in which the public amenities are marking the high-tech sector of the overarching building. The public amenities which are commonly spread on a 2-D membrane as part of an isolated campus, are in this case weaved through a stacked lobby, in which it marks the transition between the open city center and the new injection of an high-tech campus within. To emphasize this connection of a campus in the city, the rather private clean- and production rooms are connected to the urban fabric in a semi transparent way, to express the identity and fade the borders between them. This is also with the conviction that certain necesseties of a function, allows them to be used in its architectural expression, in this case the 24-hour bright articifical light of a cleanroom.

By switching the orientation of the former privatized park of the plot area towards the north-west, it opens itself to the main pedestrian flow of the city, especially the one relative to the central station. Thereby, the square of the Schouwburgplein involves itself spatially to the new public addition, in which its own amenities form an extension to the package of amenities which comes with a common campus. The transparant northern and southern facade also form a new diagonal orientation of the plot, both visually as spatially, in which this diagonal provides an open connection towards the Lijnbaan, to start regaining the former flamboyance of the latter by allowing surrounding areas to act more towards its rather isolated vein.

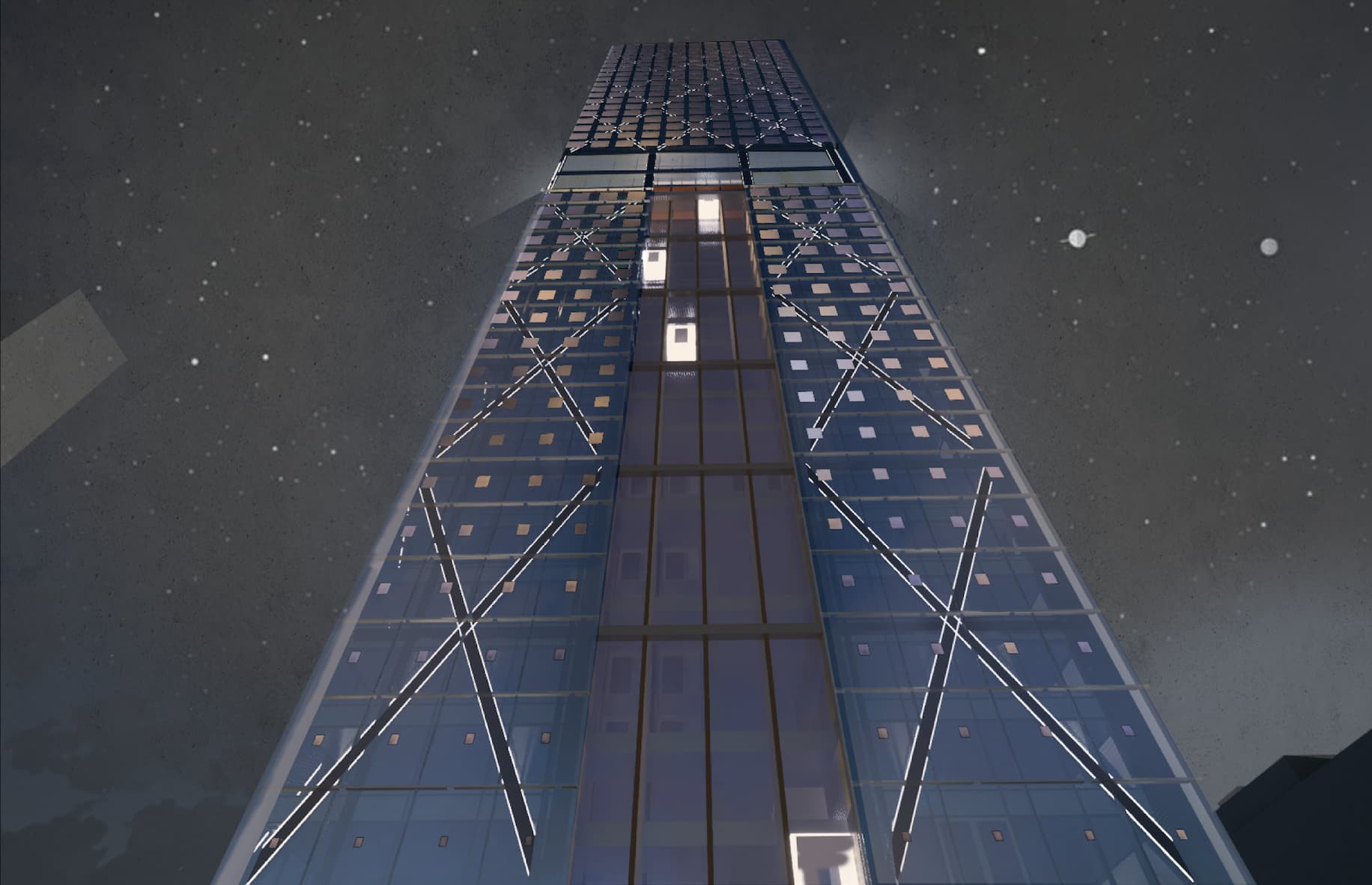

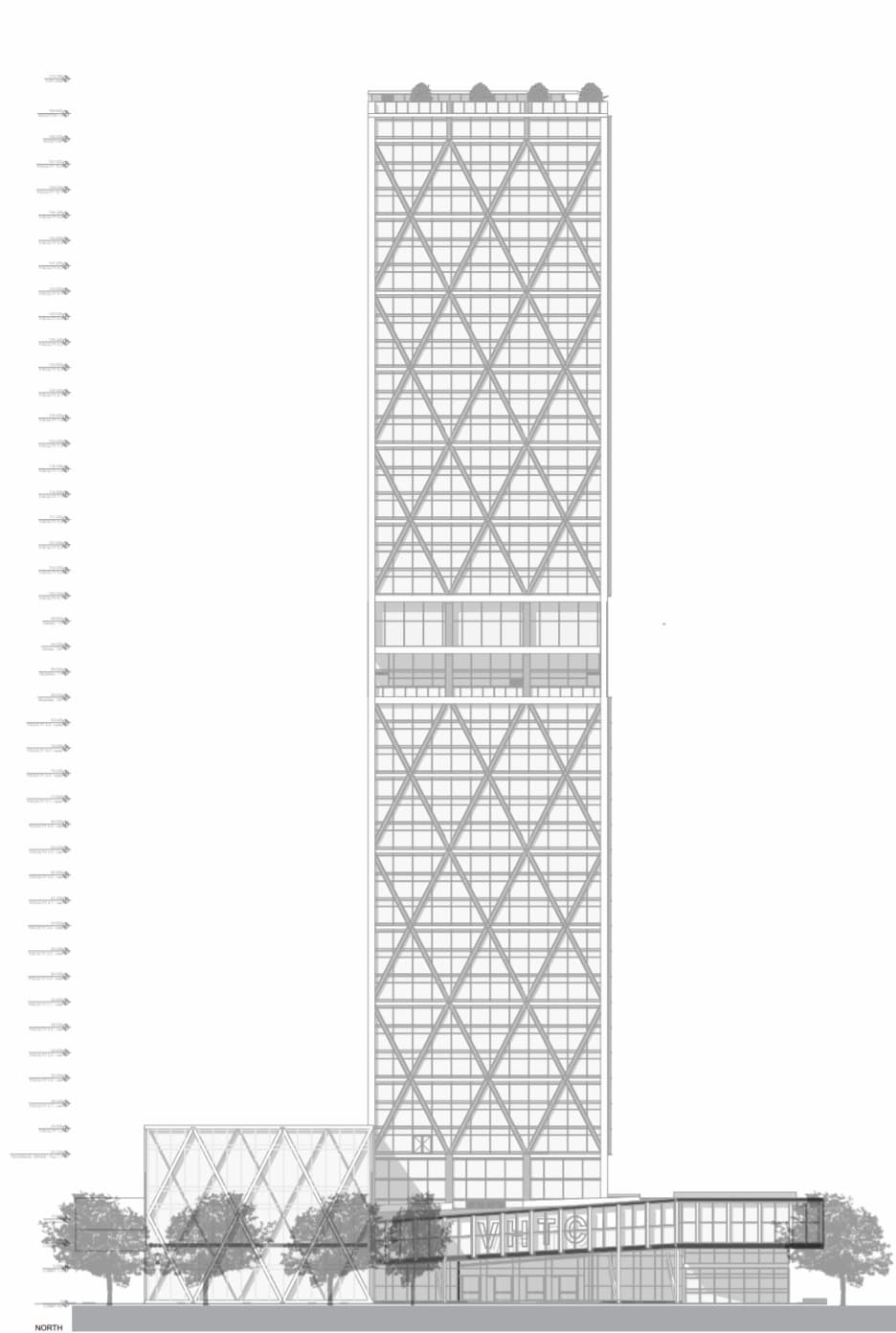

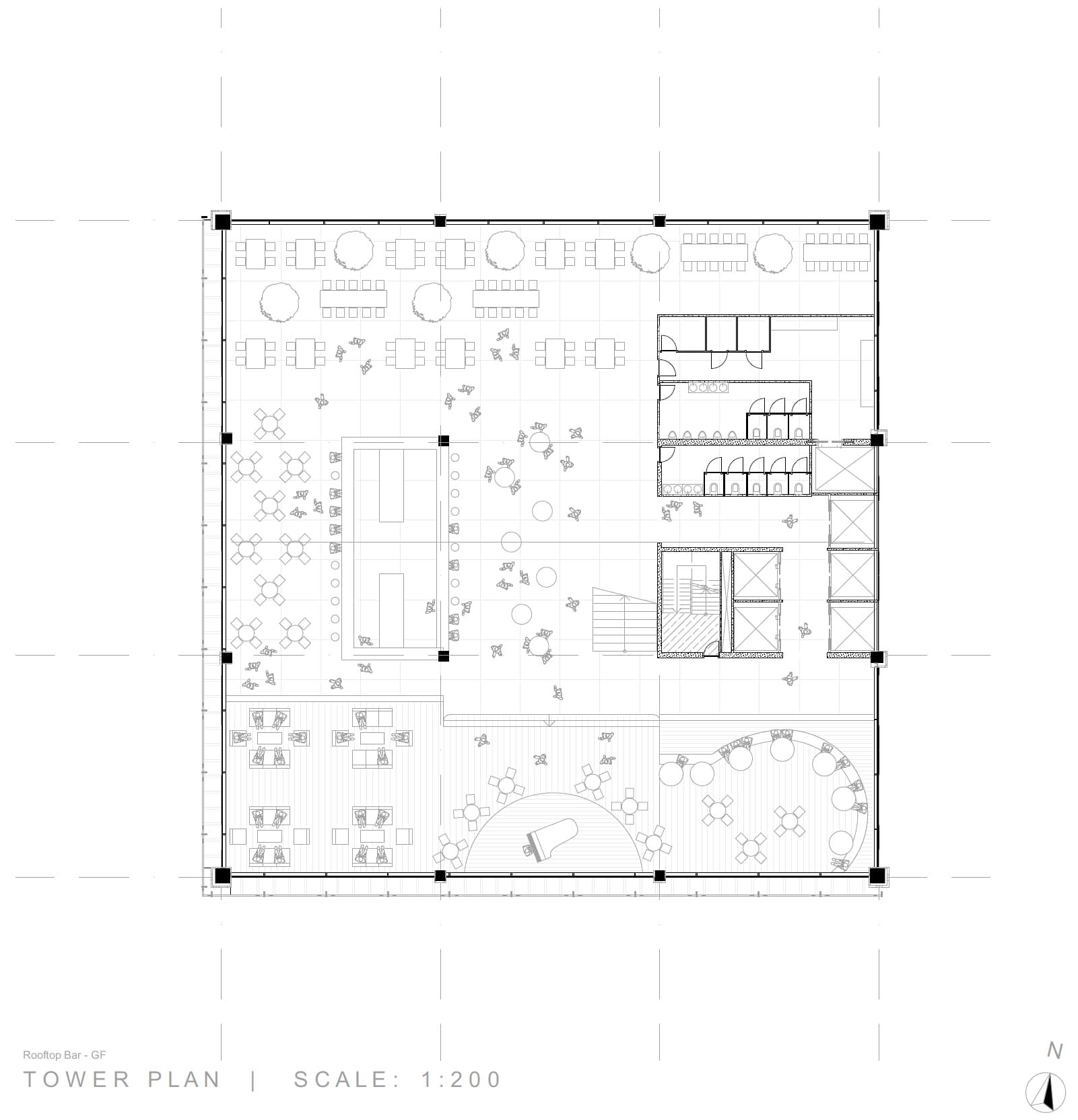

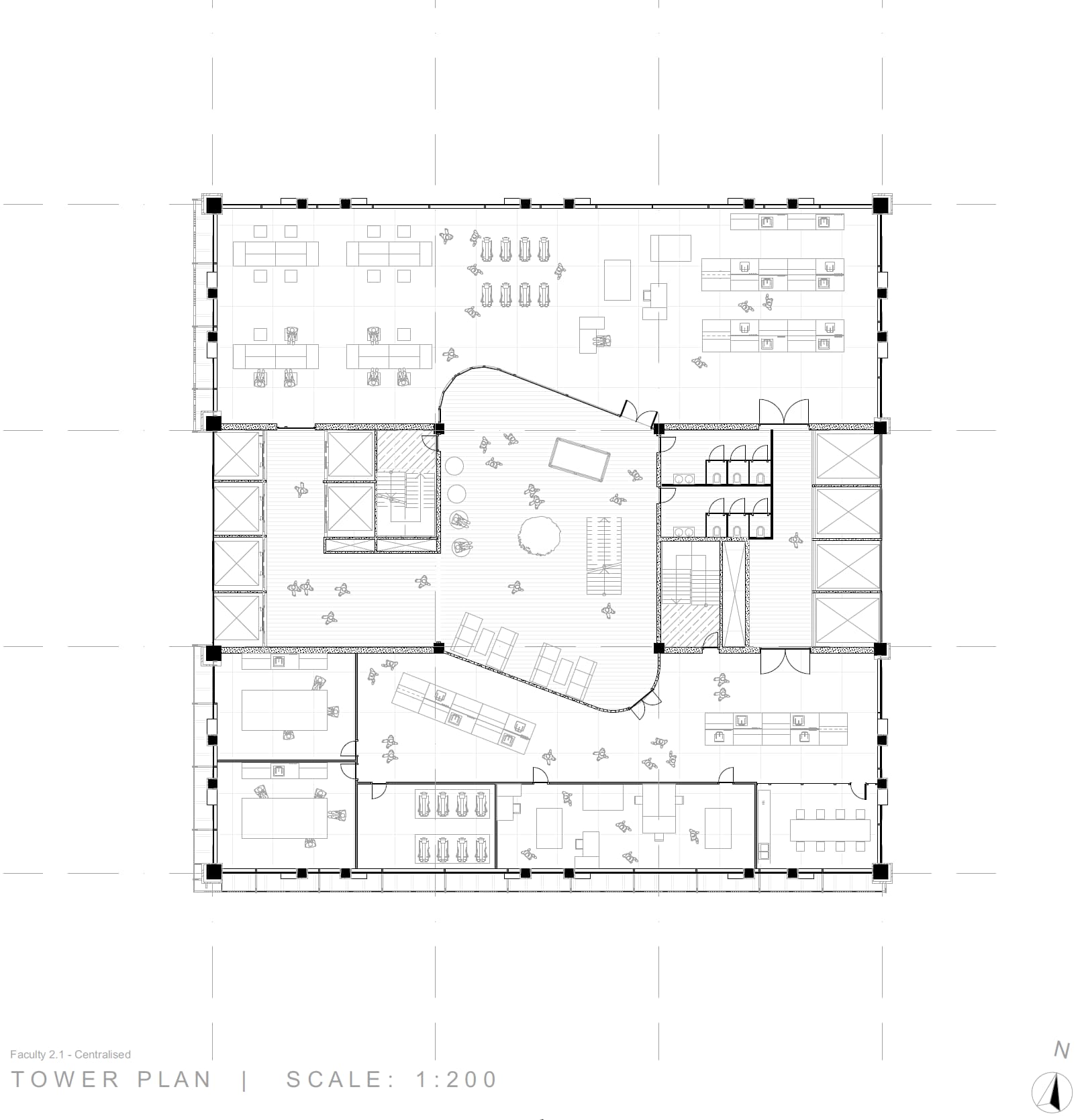

The tripartite in the tower expresses a division of functions in the exterior. Closed production rooms at the bottom, open offices at the top and a sky lobby in the middle which connects the two segments by the vertical movement in the campus. The diagrid structure allows a vertical transport system near the outside, to open up the interior and expressing liveliness from the outside. The importance of a campus is that it represents a small village with incidental meetings. In the tower, the sky lobby serves as the central square of a select domain of villagers, connecting the hybrid faculties within a packed shell. This square becomes especially a primary vein of the building, in such that the vertical movement at one side of the facade only reaches half the height of the building. In here, the sky lobby serves not only as a stacked connector, but also as a movement connector, which provides great advantages in mobility. To express its importance as a 'central square', the skylobby acts as an open beacon of light, dividing the gradation of openness in the facade.